Feb 19, 2026

On the witness stand

On Wednesday, I woke up and went through my unofficial routine. Though it’s a habit I don’t like to admit, I started my day by opening Instagram and mindlessly scrolling until I willed myself to stop and press play on a podcast instead.

That podcast opened with an ad for Instagram’s “Teen Accounts” feature, promising safeguards for kids and peace of mind for parents. The irony wasn’t lost on me: I was getting ready to head to Los Angeles Superior Court, where Mark Zuckerberg, chief executive officer of Instagram’s parent company, Meta, was set to testify in a landmark trial over whether social media is addictive and harmful to young users.

I first posted on Instagram at 16. Though I’m not quite the social media native that my Gen Z peers are, I’ve been a longtime user of the photo-sharing app and have wrestled with that question. Now, it was central to a high-stakes legal battle that could result in billions of dollars in potential damages. And I would be among the few in the room to watch Zuckerberg take the stand and answer how Instagram was designed, how it captured and retained users, and whether it caused them harm, with a particular focus on teenage girls.

This was a years-in-the-making moment. Lawyers have long been building their case against Meta, as well as Alphabet’s YouTube, Snap and TikTok — though the latter two are no longer participating after reaching confidential settlements before the trial began. The case centered on a woman named Kaley, who was on Instagram as early as 9 years old, and on claims that the app fueled years of her mental health struggles.

Inside the courtroom, the air was tense and quiet, sprinkled with grieving family members who say they lost children to the harms of social media, and reporters. In the first row was Kaley, who had so far been absent from the trial. Now 20, she sat directly in the line of sight where Zuckerberg would soon testify.

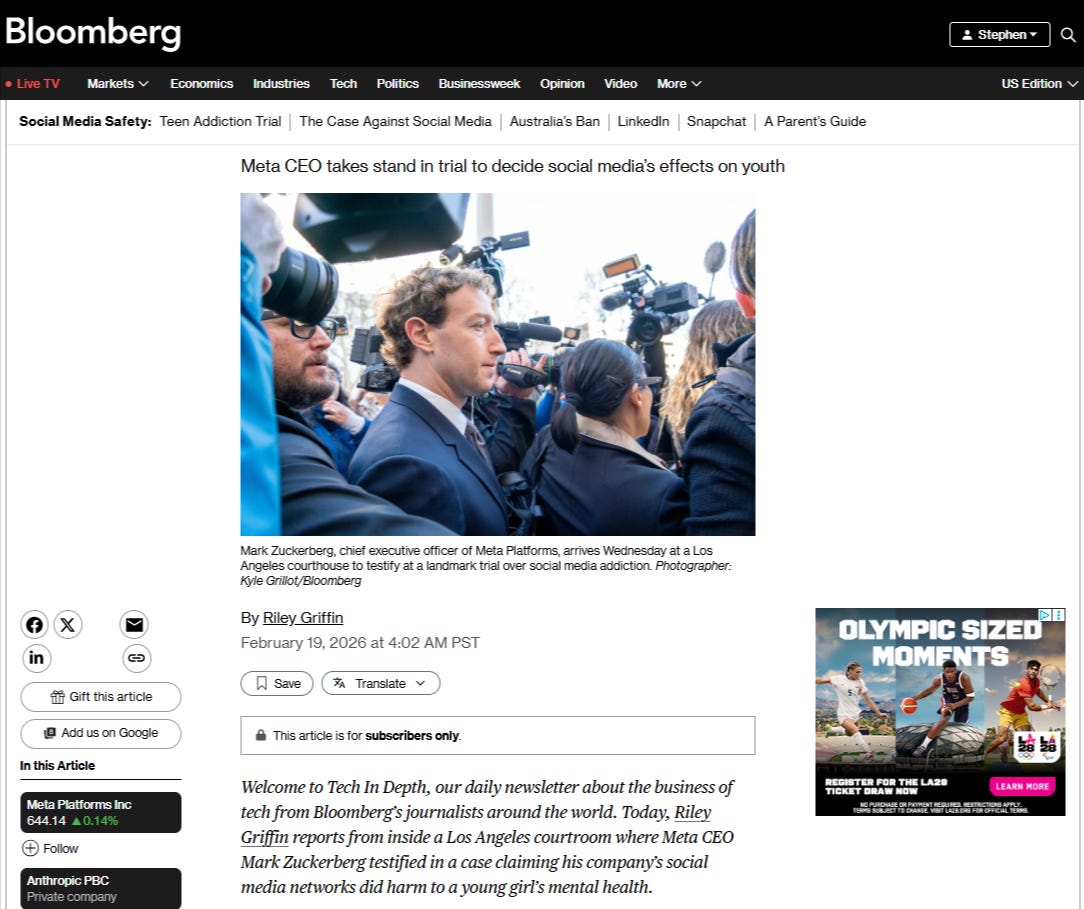

When the CEO and fifth-richest man in the world arrived, many in the room failed to notice. Dressed in a dark blue suit and gray tie, Zuckerberg looked somber, subdued. As he approached the stand, nerves broke through. He fidgeted with a water bottle and took a deep breath.

This was the calm before the storm.

For six hours, Zuckerberg faced a barrage of questions about his company’s effort, or lack thereof, to protect young users on Instagram and Facebook. He was pressed on internal communications in which employees pleaded to shore up safety measures, and lamented the toll social media took on children. He was questioned about Meta’s focus on increasing the amount of time users spent on its platforms, and the company’s knowledge that a broad swath of pre-teens were on the apps despite stated restrictions for those younger than 13. He was made to look at a banner depicting an unfathomable number of selfies Kaley had posted throughout her youth. And pressed on choices he made about beauty filters.

Though Zuckerberg has faced challenging inquiries from Congress and federal lawyers before, this was the first time he testified about social media’s impact on mental health before a jury. His responses were slow, often quiet, acknowledging past practices, while promising many had changed. He spoke of balancing guardrails with his north star of free expression. He noted that teens currently account for just 1% of the company’s revenue, given their lack of disposable income, but suggested he still wants to deliver them “value,” which he claimed was necessary to keep them on the platforms for the long term.

The day was an exhausting back-and-forth, where Zuckerberg was dealt some blows and scored some wins. By the end, he appeared tired: checking his watch, flickering his eyes, and responding in a muted tone unlike the one I’ve heard at company conferences, on earnings calls, or across his own social feed.

Zuckerberg’s testimony didn’t settle the question of whether social media is addictive, for Kaley or any of its users. But it did thrust into the spotlight the different choices that could have been made. Meta could have done more to enforce its age requirements, for example, or realized earlier on that optimizing its product for “time spent” was a bad idea. Zuckerberg said the company has evolved on both fronts, but I wonder if that evolution happened too late.

Those questions will continue to loom over the trial as it moves forward into next month. And it could prove a critical test not only for Meta, but for the thousands of similar cases winding through courts across the country; cases that could shape the future of Instagram itself, the app so many of us still reach for before we’re fully awake.