Newspaper Reader

Oct 25, 2025

Editor: My apologies to my readers, for the inordinate length of my collection of my various comments, on the question of Argentine Politics. I was happy that my recall and memory are somewhat reliable when pressed to the limit! I will make revivions!

The Americas | Argentina’s future

Headline: Javier Milei’s fate turns on an upcoming election. Can he win?

Sub-headline: It is a battle to be the least disliked

…

Never before have midterm elections in Argentina grabbed so much global attention. The Trump administration has thrown the financial might of the United States behind both President Javier Milei and the Argentine peso, turning the vote on October 26th into a political football in Washington and front-page news in the rest of the world. Bond markets scrutinise every poll. Yet one crucial group seems uninterested: the Argentines.

In Buenos Aires, the capital, billboards are rare, rallies are modest and apathy is widespread, even at campaign events. “I’m obliged to be here,” says Emiliano, who is walking in a small march for Peronism downtown. The distant Peronist-run municipality that he works for as a street cleaner brought him there. Who will he vote for? “I don’t know.” Every major political leader, including Mr Milei, is viewed negatively by a majority of Argentines. “In New York there is much more interest in the election than here,” says Gala Díaz Langou of CIPPEC, an Argentine think-tank, who recently visited Wall Street.

Reader note that the Economist frames it’s News Story: looks first to the anonymous Emiliano that works for as a street cleaner, as opposed to Gala Díaz Langou of CIPPEC, an Argentine think-tank. Oxbridgers are steeped in Class Bias, this cannot surprise the regular reader !

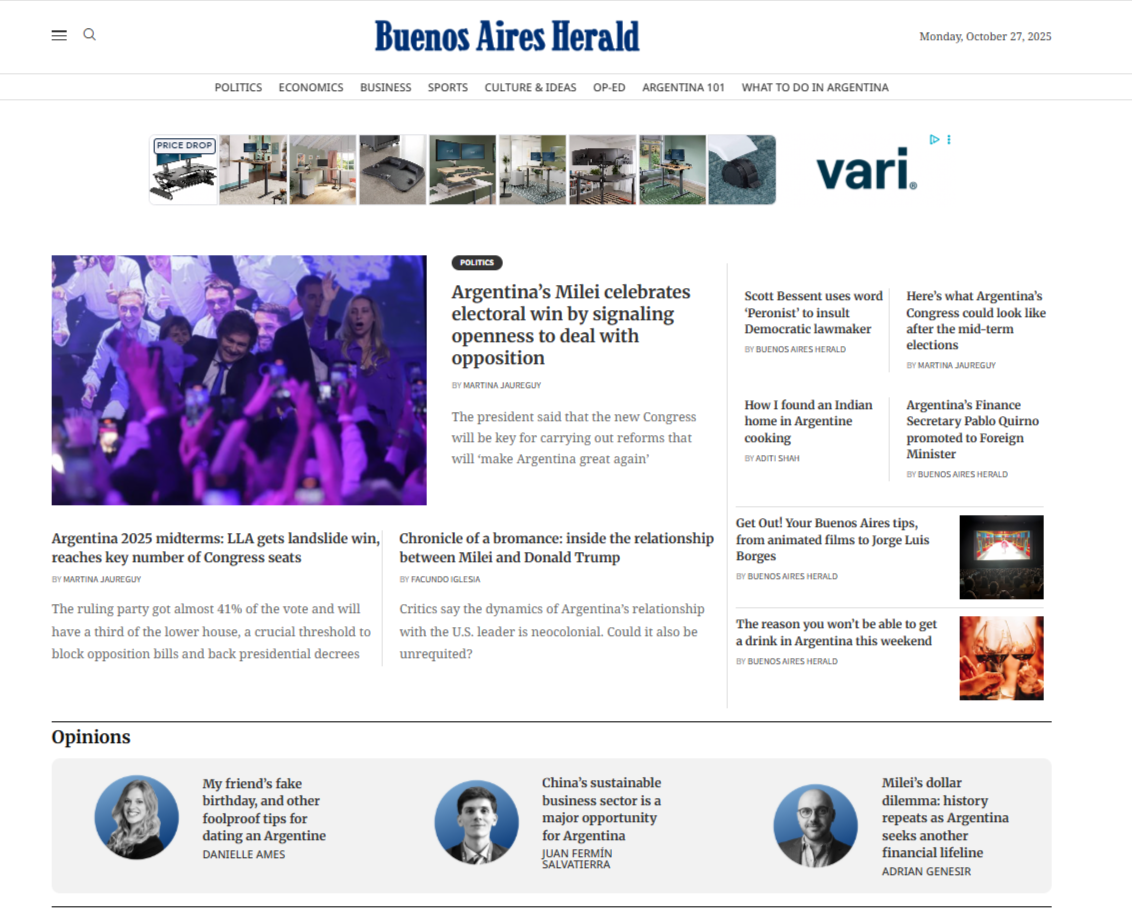

Editor: Look to the Buenosaires Herald as a more reliable source of information about Argentine political life?

Headline: Milei’s dollar dilemma: history repeats as Argentina seeks another financial lifeline

Sub-headline: As Argentina receives US backing amid political turmoil, echoes of past failed rescue attempts raise questions about the libertarian president’s future.

Adrian Genesir

October 1, 2025

Argentina once again finds itself at a familiar crossroads. Past week, President Javier Milei’s government announced a potential $20 billion currency swap lifeline from the United States, just as financial pressures and electoral setbacks mount. The deal, confirmed by US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent, adds another chapter to Argentina’s century-long cycle of crisis and foreign bailouts – a cycle that rarely delivers lasting stability.

The timing could not be more critical. On September 7, Milei’s La Libertad Avanza suffered a crushing 13-point defeat to Peronist forces in Buenos Aires Province, securing just 34% of the vote compared to the opposition’s 47%. Markets panicked: the peso fell to its exchange rate ceiling, while country risk spiked above 1,100 basis points.

The parallels with the past are striking. Fernando de la Rúa’s “blindaje” (shield) in 2000 and “megacanje” in 2001 initially calmed markets but failed to prevent collapse. Mauricio Macri’s record $57 billion IMF package in 2018 financed capital flight without restoring growth, setting the stage for his 2019 defeat. Milei, like them, has tied his legitimacy to exchange-rate stability while imposing painful fiscal cuts. The Central Bank has already spent over $1 billion defending the peso, recalling the reserve depletion that preceded the 2001 meltdown.

The irony is hard to miss. Milei, who campaigned on eliminating the Central Bank, now depends on it as his main tool – a point his critics, like Buenos Aires Governor Axel Kicillof, emphasize. The libertarian who promised to free dollar markets now bends policy to control them.

Recent export tax maneuvers highlight this contradiction. On September 22, weeks before the October 26 elections, the government suspended grain export taxes until October 31 or until $7 billion in sales were declared. The rush was immediate: quotas were filled in three days, with over 11 million tonnes exported on September 24 alone. Yet the policy was reversed within 72 hours, leaving farmers frustrated and reinforcing perceptions of opportunism.

You may also be interested in: End of tax holiday sparks producers’ concerns over local soybean prices

At the ballot box, Milei faces another structural problem: his ceiling of support. He won the presidency in 2023 with only 30% in the first round, and that number has barely budged through 2024’s local elections. Even his Buenos Aires City legislature victories were won with about 30%. The recent 34% in Buenos Aires Province suggests his base is loyal but capped.

The October midterms may shift the equation. Of 257 lower house seats, 127 are up for renewal, and Milei’s coalition is defending just 7. In the Senate, all 24 seats at stake belong to opposition parties. Structurally, this favors Milei, giving him a chance to expand his footprint without risking much.

Yet gains would likely come at the expense of Mauricio Macri’s PRO rather than Peronism. LLA has already overrun PRO’s Buenos Aires City strongholds. While the two coordinate campaigns, tensions over post-election seat distribution loom. Congress has already exposed the alliance’s weakness, with PRO legislators sometimes siding with opposition overrides despite theoretical support for Milei.

If the alliance fractures, PRO may hold traditional enclaves, while Milei dominates anti-establishment districts. The result could leave both weakened against a unified opposition. Meanwhile, Milei’s reliance on young voters, who lack memory of past crises and evaluate leadership through immediate conditions and social media, makes him vulnerable to rapid shifts. Allegations involving his sister Karina spread quickly online, damaging his credibility.

History offers a sobering warning. Technical fixes – whether swaps, shields, or bailouts – cannot substitute for political legitimacy. The $20 billion from Washington may buy time, but without coherence between promises and practice, Milei risks repeating his predecessors’ fate. Each failed attempt deepens public mistrust of market reforms, narrowing the path for future leaders.

Whether Milei breaks the cycle depends less on foreign lifelines than on domestic politics: uniting his fragile coalition, managing the alliance with PRO, and broadening his appeal beyond a fixed base. If he fails, Argentina’s story may rhyme once again with its past – another rescue that saved time, but not the project.

Editor: Reader make note of The Economists waning political romance with Javier Milei. Zanny Menton Beddoes and her fellow Neo-Liberals are no doubt anguisged by the reality of the Fall of Milei ? Though one short mournful paragraph seems …

Mr Milei won office in 2023 by exciting voters with radical plans and furious condemnation of “la casta”, the political class. Since then, huge cuts to spending have pulled monthly inflation down from 13% to about 2%. Poverty has fallen to its lowest level since 2018. Mr Milei has slashed red tape, improving everything from internet access to airlines. At the start of the year it looked as if he had a good shot at a thumping win in the midterms, where half the seats in the lower chamber and a third of those in the Senate are up for grabs. Now, Mr Milei’s project is at risk of unravelling.

…

Editor: Here is my comment of March 30, 2017 on Macri’s Austerity, yet the result of the resort to the IMF defines what is the Argentine political leitmotif !

Macri’s Austerity and Macron Neo-Liberalism with a Human Face: a comment by Old Socialist

Posted on March 30, 2017 by stephenkmacksd

I haven’t read anything in the American Press about the political unrest in Argentina. America’s political narcissism is primary, and the outliers in South America hold no purchase on the crisis ridden Age of Trump.

Yet Macri’s exhumation of Neo-Liberalism and his bribing of Vulture Capitalist Paul Singer, as entree back into the World Economic family, seems to be in actual political trouble. The best the Financial Times can do, in the realm of an Argentine political ‘experts’, are Fernando Iglesias and Maria Victoria Murillo, an Argentine political scientist at Columbia University. Neither one a Peronist! And the perfect choices to give credence to the Financial Times’ Anti-Populist Party Line. The question arises what was the actual legacy of the 12 years of Kirchner government, provided here by teleSUR :

‘For Argentines, just as the 1980s are referred to as the “lost decade,” the 12 years of Kirchner government (four by the late Nestor Kirchner and eight by Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner) is now often called the “won decade.”

The Kirchner governments found success in systematically improving the everyday lives of Argentines. Social policies, such as subsidies, pension raises and unemployment benefits, went hand in hand with the improved economy, as well as the necessary and popular overhaul of Argentina’s judicial system after the murky history of human rights abuses committed with impunity.

Nestor Kirchner was also a key figure in the regional integration of Latin America. He was the leader who managed to restructure 93 percent of the country’s massive debt, Fernandez took the baton and heroically battled the remaining 7 percent demanding repayment, known as the vulture funds.’

Fernando Iglesias extemporizes on the theme of Peronist rabble rousing, indeed on the tradition of ‘coup-mongering’ in Argentina:

‘Even so, Fernando Iglesias, a writer and former congressman who supports the government, argues that this is Mr Macri’s “most difficult moment” so far.

“People still don’t have money in their pockets, and of course the Peronist opposition is taking advantage of this with strikes, demonstrations and roadblocks . . . There is a long history of coup-mongering in Argentina,” warns Mr Iglesias, pointing to the failure of all non-Peronist governments to complete their electoral mandates since the return of democracy in 1983.

…

“The Peronists know that if the country recovers they will never return to power. The stakes couldn’t be higher, so they are going all in,” adds Mr Iglesias. Indeed, many senior figures from the previous government face corruption charges, including Ms Fernández herself, who is due to stand trial soon for the first of various cases against her.’

What the reader gets near the end of this extended apologetic on behalf of the Neo-Liberalism of Macri, is this collection of data, that should have mollified even the most ardent Populist? This notion is in the realm of the chatter of the technocrat.

‘Officials complain that the timing of the general strike makes no sense. Despite a 2.3 per cent decline in gross domestic product overall in 2016, in the third and fourth quarters the economy grew by 0.1 per cent and 0.5 per cent respectively compared to the previous quarters. Since October, around 25,000 jobs are being created each month, say officials.’

What is more than compelling in terms of argument is Maria Victoria Murillo’s comment that at first attempts to trivialize the strikes as:

‘…argues that the general strike is “not a big deal” and is “nothing new.” She explains that the leaders of Argentina’s fragmented trade unions need to flex their muscles from time to time to maintain support among the grass roots.’

And then she asserts that:

“It may have an impact on the margins, but ultimately the election will be decided by the economy,” says Ms Murillo. “Unless they can solve that, they are toast — the rest is decoration.”

Mr. Macri’s success is dependent on an electorate that is, to say the least, unhappy with his expression of Austerity, that is one of the central tenets of the Neo-Liberal Dispensation, dubbed ‘Reform’ by its acolytes. It would have been the wiser course, to have offered to Argentina what Macron is offering to the French electorate: Neo-Liberalism with a Human Face, e.g.:

‘The candidate’s recently announced programme is thus a careful balancing act between progressive ideals of social solidarity and conservative aspirations to entrepreneurship and order: it includes a raft of liberal economic proposals, such as cutting public expenditure, reducing the number of civil servants, unifying the pension system, and introducing greater flexibility in the labour market. But it also contains socially progressive measures, such as increasing the number of teachers, offering additional resources to schools in disadvantaged areas, promoting greater equality between the sexes, protecting those on short-term employment contracts, abolishing the residence tax for 80 per cent of the population, and offering a “Culture Pass” of €500 to all eighteen-year-olds – a concrete affirmation of Macron’s republican belief that education and learning are “the apprenticeship of freedom”.

The metaphor is revealing, for at the heart of Macron’s vision lies the promise of an “enterprising and ambitious France”. His conception of the good life is that of an optimistic, cosmopolitan and socially conscious modernizer: committed to the transformation of the French economy, and releasing business from the burdens of high taxation and over-regulation, but also aware (not least as a child of the provinces) that the market alone cannot produce equal opportunities for all citizens, and that state intervention is often indispensable.’

http://www.the-tls.co.uk/articles/public/emmanuel-macron-revolution/

Old Socialist

https://www.ft.com/content/81e544a4-12fa-11e7-80f4-13e067d5072c

Editor: Here is a collection of my comments:

At The Financial Times: Mauricio Macri’s Neo-Liberal Reform stalls, a comment by Old Socialist

Posted on August 31, 2016 by stephenkmacksd

What might a reader take from this review of The Panama Papers by Edward N. Luttwak, published by The TLS of August 17,2016 titled ‘Hidden assets, hidden costs’? A long quotation from the essay is not just revelatory about the corruption of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, but that of Neo-Liberal White Knight Mauricio Macri, who was also customer of Mossack Fonseca. Note that Vulture Capitalist Paul Singer rates a mention as rabid pursuer of assets, that even eluded his greed:

‘The Panama Papers opens with an engaging first-person account by Bastian Obermayer, a well-known investigative journalist for the Süddeutsche Zeitung, of how the whole story started: an unsolicited email from a John Doe offering “data”. As soon as Obermayer accepted the twin conditions of total anonymity and encrypted communications, he received “a big bunch of documents”.

These mostly concerned the alleged smuggling of $65 million out of Argentina on behalf of its President, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner – hardly startling news if true, given the country and the person but the documents also included what really mattered: full corporate information on the 123 name-plate-only (“shell”) companies that were used to zig-zag the money surreptitiously around the world, all of them formed by a Panamanian law firm called Mossack Fonseca.

If anyone tried to work back from company number 123 to the original money-sending company by way of the 122 companies in between, a lifetime of investigations might not do it, especially because those 122 companies could be registered anywhere in the world, not restricted to the places where Mossack Fonseca had and still have offices, to wit: Anguilla, the Bahamas, Belize, the British Virgin Islands, Costa Rica, Cyprus, Hong Kong, Malta, the Netherlands, Panama, Samoa, the Seychelles, the United Kingdom and two US states: Nevada and Wyoming. Those companies, moreover, could be legally incorporated yet have no identifiable owners at all, because their equity might all be vested in nameless “bearer” shares. Not even the ultra-formidable billionaire Paul Singer, who had bought up heavily discounted Argentine debt, had refused “haircut” payouts and was employing lawyers and investigators everywhere to track down anything of value that he could impound (he did succeed with an Argentine naval vessel), could do anything about the $65 million sitting tantalizingly close to him in Nevada – but now all the data was revealed (too late for Singer because Argentina’s new President, Mauricio Macri, also a Mossack Fonseca client as it happens, had already decided to settle and pay him off, along with all the other hold-out claimants).

At The Financial Times: On Macri’s failed attempt at the Neo-Liberalization of Argentina. Political Observer comments

Posted on May 10, 2018 by stephenkmacksd

It was a stunning reversal for the 59-year-old former businessman who came to power in December 2015 vowing to make Argentina a “normal country”, after 12 years of leftist rule by Mr Kirchner and his wife Cristina Fernández.

Not ‘normal country’ ! Macri paid a ransom to Vulture Capitalist Paul Singer, as the admission price to the utterly dysfunctional Family of Neo-Liberal Nations!

Two days ago, in this newspaper, there were at least three ‘news stories’ about the present Argentine Crisis that I read, two of those ‘reports’ had disabled comments sections. There is nothing this newspaper fears more than The Rebellion Against The Elites, except the open contempt of its readership! Those ‘news stories’ brimmed with the symptoms of the ‘run on the currency’. But the pseudo-technocrats at The Financial Times demonstrate that the Dismal Science is in fact Political Economy, in the vulgar ill-fitting party dress of Statistical Data!

Austerity has never worked even in its ‘gradualist’ iteration of Macri. Wunderkind Alfonso Prat-Gay was Macri’s Minister of Finance for a short time but look at his record of achievements in ending ‘the clamp’ and the part of his record that is equally dubious :

A decade later, as Minister of the Economy of Mauricio Macri, he lifted 4-year-old government controls on the Argentine currency (“the clamp”), a mere 4 days after taking office.[4]

…

Prat-Gay was appointed minister of financed in 2015, by president Mauricio Macri. In that capacity, he successfully ended the currency controls established by Cristina Kirchner and the sovereign default declared in 2001. He also helped to restore international relations, and the update of the figures of the wealth tax, which had not been updated in previous years in line with inflation. He had conflicting views of the economy with Federico Sturzenegger, president of the Central Bank of Argentina. By demand of president Macri, he resigned on December 26, 2016,[15] and was succeeded by Nicolás Dujovne.[16]

…

Prat-Gay was appointed minister of financed in 2015, by president Mauricio Macri. In that capacity, he successfully ended the currency controls established by Cristina Kirchner and the sovereign default declared in 2001. He also helped to restore international relations, and the update of the figures of the wealth tax, which had not been updated in previous years in line with inflation. He had conflicting views of the economy with Federico Sturzenegger, president of the Central Bank of Argentina. By demand of president Macri, he resigned on December 26, 2016,[15] and was succeeded by Nicolás Dujovne.[16]

Could the removal of ‘the clamp’ and the ‘gradualism’ of the Austerity of Macri be the root of the present Argentine Crisis?

…

Posted on December 8, 2020 by stephenkmacksd

From the early days of The Economist’s Political Romance with Mauricio Macri.

From January 2, 2016

Headline: A fast start

Sub-headline: Mauricio Macri’s early decisions are bringing benefits and making waves

‘MAURICIO MACRI, who took office as Argentina’s president in December, has wasted little time in undoing the populist policies of his predecessor. On December 14th he scrapped export taxes on agricultural products such as wheat, beef and corn and reduced them on soyabeans, the biggest export. Two days later Alfonso Prat-Gay, the new finance minister, lifted currency controls, allowing the peso to float freely. A team from the new government then met the mediator in a dispute with foreign bondholders in an attempt to end Argentina’s isolation from the international credit markets.

This flurry of decisions is the first step towards normalising an economy that had been skewed by the interventionist policies of ex-president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and her late husband, Néstor Kirchner, who governed before her. They carry an immediate cost, which Mr Macri will seek to pin on the Kirchners. Some of the new president’s other early initiatives are proving more controversial.’

…

‘Touring northern Argentina, where 20,000 people have been displaced from their homes by floods, Mr Macri blamed the former president, saying she had failed to invest in flood defences (see article). For now, Argentines are likely to believe their new president. However, if the economic slowdown is prolonged, the honeymoon will not be.

https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2016/01/02/a-fast-start

__________________________________________________

From August 11, 2016

Headline: It’s cold outside

Sub-headline: A battle over utility bills is Mauricio Macri’s first big crisis

THE most populous parts of Argentina are stifling in summer and bone-chilling in winter. The Kirchner family, which ruled for a dozen years until 2015, kept the cost of comfort low. An earlier government had fixed the price of electricity and natural gas in 2002 to help the economy out of a slump; the Kirchners barely raised it. As a result, Argentines pay a fraction of what their neighbours do for energy (see chart).

But they have paid in other ways. Energy subsidies jumped from 1.5% of government spending in 2005 to 12.3% in 2014. Partly because of such largesse, the budget deficit was a worrying 5.4% of GDP last year. Because energy is cheap, consumers use it with abandon; utilities lack cash for investment. Summer blackouts can last for hours. Mauricio Macri, who succeeded Cristina Fernández de Kirchner as president in December, said the energy crisis was the most complex of the “many bombs” she had left for him. Defusing it is proving to be perilous.

…

Mr Macri has little choice but to hope that the supreme court rules in his favour, persist with price rises and pay the political cost. “To find tariffs both attractive enough for investment and acceptable to society—without impacting inflation—is impossible in the short term,” says Carlos Marcelo Belloni of IAE Business School in Buenos Aires. Like chilly consumers, Mr Macri is waiting for balmier weather.

https://www.economist.com/the-americas/2016/08/11/its-cold-outside

____________________________________________________

From September 23, 2016

Headline: How Mauricio Macri is trying to rehabilitate Argentina’s economy

Sub-headline: The president faces a vast task

FOR most of 2015 few gave Mauricio Macri much chance of becoming Argentina’s president. The pro-business mayor of Buenos Aires lagged in the polls behind Daniel Scioli, the candidate favoured by Argentina’s outgoing president, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. Pundits pointed out that no non-Peronist president had completed a full term in office since 1928. But in the end it was Mr Macri’s outsider status that clinched his victory. After scraping 51% of the vote in a run-off on November 22nd, his supporters at home and abroad looked forward to swapping political populism for economic prosperity. But, more than nine months after his inauguration, Argentina is still plagued by high inflation, unemployment and weak consumer demand. What has gone wrong?

The scale of the task confronting Mr Macri was formidable. Argentina had been a financial pariah for more than 14 years, cut adrift from international capital markets thanks to a long-running dispute with holders of its defaulted debt. Official government statistics were widely discredited, prompting the International Monetary Fund to issue a formal censure in 2013. A standoff with the agricultural sector meant that farmers preferred to stockpile grain and soyabeans rather than export them. Currency controls left the peso overvalued and foreign exchange reserves at a nine-year low. Years of chronic underinvestment in infrastructure had pushed the country’s energy network to the brink of collapse.

…

The new president favoured bold action. During his first weeks in office Mr Macri eased currency controls, reduced export tariffs on agricultural goods and oversaw an overhaul of the national statistics institute. In April he concluded a $9.3 billion deal with holders of Argentina’s defaulted debt, restoring the country’s access to credit markets. But the remedies, although necessary, have proved painful. The peso’s devaluation pushed up the already-high inflation Mr Macri had inherited to around 40%, the highest rate in Latin America outside Venezuela. The reduction of unaffordable energy subsidies and an accompanying rise in utility bills inflicted more pain on hard-pressed consumers. With unemployment at 9.3% and the economy in recession, union-organised protests brought tens of thousands of demonstrators onto the streets of Buenos Aires on September 2nd.

Mr Macri is desperate for good news. With legislative elections due in October 2017, his political fortunes will hinge on whether or not Argentines begin to feel tangible improvements in the economy. Inflation is finally slowing: in August prices rose by just 0.2%. But the flood of foreign investment Mr Macri promised would arrive following Argentina’s return to the markets has so far failed to materialise. For now at least, experts remain optimistic. Although the IMF believes the economy will shrink by 1.5% of GDP this year, it forecasts growth of 2.8% for 2017. Argentines also appear willing to give Mr Macri the benefit of the doubt. After months in decline the president’s approval ratings have stabilised at 56% over the past two months, according to Poliarquía, a pollster. As spring arrives in Buenos Aires, Mr Macri must be hoping that his fortunes have finally turned.

…

Editor: I have attemped to condence the Economist political melodrama to its essientials?

The slide began in February, when he promoted a dodgy cryptocurrency which soon collapsed in value.

…

Mr Milei also relied heavily on a strong peso to pull down inflation, even after floating it within bands in April as part of an IMF bail-out. He assumed that low inflation would win the election.

…

All this came to a head on September 7th with legislative elections in Buenos Aires province, home to 40% of the population. Mr Milei’s party, Liberty Advances (LLA), lost to the incumbent Peronists by 14 percentage points. Markets panicked and ditched pesos.

…

It stumped up in extraordinary fashion: a $20bn swap line, almost $1bn in peso purchases and an effort to corral another $20bn from private banks. Yet, as The Economist went to press, the peso was still under heavy strain.

…

Mr Milei is also more popular in the interior of the country than in the province of Buenos Aires. Many voters will still reward him for reducing inflation.

….

“I don’t know the candidates really, I’m voting for Milei,” says Ezequiel Salazar, a young interior designer. LLA will need lots of voters to focus similarly on Mr Milei rather than his candidates.

…

Mr Milei’s outsider, anti-corruption brand may have been broken by these repeated scandals, says a well-connected political consultant.

…

The perceived assault on Argentine sovereignty may fire up the Peronist base. “We don’t have a president, we have a guy receiving orders,” fumes Óscar Rubén from La Matanza, a Peronist bastion in the outskirts of the capital.

…

The biggest issue is the weight of Argentines’ wallets. “What good are falling prices if people haven’t got work,” says Mr Rubén.

…

People are focused on keeping their heads above water, says María Jimena López, a leading Peronist candidate in the province of Buenos Aires. “They see that every day the water keeps rising.”

This leaves an unusually wide range of possible outcomes. Markets will tumble if, together with his allies, Mr Milei fails to marshall the third of the seats in the lower chamber that he needs to prevent his vetoes being overturned. If his party polls below 30%, then chaos will ensue, especially because Mr Trump hints that he may walk away if Mr Milei loses.

…

“Whatever the outcome, the instability disappears,” says Federico Sturzenegger, the minister for deregulation. Yet even with more seats, if Mr Milei’s approval rating is low he will struggle to control Congress.

…

Even a narrow win that forces Mr Milei to rely on somewhat friendly parties to defend his veto may suffice to prevent initial market panic. Pollsters suggest that is the most likely result (see chart), though they were badly over-optimistic about his chances in the Buenos Aires provincial election.

…

The most obvious ally will remain the PRO, the right-wing party of a former president, Mauricio Macri. But it will not roll over. “The conditions will be onerous,” says Fernando de Andreis, who was Mr Macri’s chief of staff, “even more than those of the last year and a half.” A fiendishly difficult two years beckons.

October 27, 2025

Editor : The Economist seemed to be in doubt of Javier Milei power, and so was I!

The Americas | Argentina’s future

Headline: Javier Milei’s fate turns on an upcoming election. Can he win?

Sub-headline: It is a battle to be the least disliked