Political Observer.

Oct 09, 2025

Editor: Reader begin your political education about Beddoes here!

Dr. Jeffrey Sachs, Shock Therapist

By Peter Passell

June 27, 1993

The lobby of the Metropole, Moscow’s lovingly restored grand hotel a few blocks from Red Square, is almost deserted on this gray spring afternoon. That’s just fine with Jeffrey D. Sachs, a boyish-looking 38-year-old Harvard professor who is now probably the most important economist in the world. He has appropriated a cluster of comfortable armchairs for a meeting with two members of his team, Americans who work full time in Russia.

The agenda is Russia’s safety net or, more precisely, whether unemployed workers will be able to make ends meet. Russia is plunging out of Communism, if not directly into a capitalist free market. Whether this huge, humiliated nation will stoically bear the pain of the transition is far from clear, and the strength of the safety net could make the difference.

There are plenty of laws on the books, but do they count? “All Russian citizens are legally entitled to free health care,” points out Judith Shapiro, a senior lecturer on policy economics who is on leave from Goldsmith College at the University of London. The catch: they often “only get what they pay for.”

While employees of Government and big enterprises generally have access to adequate service at their own clinics, the less fortunate are denied modern surgery, drugs and even decent sanitation. The problem is apparently growing worse, she notes, because inflation has far outpaced physicians’ salaries, which weren’t high to begin with. Many are now emigrating, or deserting their posts for more lucrative jobs, like driving taxis.

Sachs’s immediate concern is the implication for the Government’s budget, which must be slashed in order to bring inflation under control. If much of the nation’s health expenditures are now buried as fringe benefits on the books of enterprises that depend on Government subsidies, who will pick up the cost once the enterprises are forced to economize?

Getting a handle on the magnitude of the problem is obviously difficult in a country that cannot even explain why life expectancy has fallen sharply in the last two decades. But some number is better than none. And by pressing officials to address this and other pivotal issues, Sachs hopes to accelerate the pace of reform.

Sachs’s message of urgency is not universally accepted. Plenty of Western as well as Russian economists contend that a more gradual approach is not only possible but necessary. “Economic reform is a political process,” says Padma Desai at the Harriman Institute at Columbia University. “First, you must build consensus.”

And even his sympathizers acknowledge that Sachs’s high profile and world-class impatience could generate a backlash in a nation still adjusting to the reality that it is no longer a superpower. “There’s a real dilemma here,” says Stanley Fischer, an international economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “You have to make a lot of noise to get the attention of the West. But the more noise you make, the more you make it seem that the reform program is a Western program. And that could be the kiss of death.”

Still, Sachs’s brand of “shock therapy” has worked elsewhere. And there is good reason to believe that Russia’s future will turn on how well its leaders learn the catechism of change that he has worked so hard to promulgate.

TO AN AMERICAN JADED BY THE CHOICE OF breakfast flakes with or without bran, dates, sugar-coated raisins and 12 essential vitamins, there’s nothing much to tease the palate or the eye in the Gastronom Smolensk near the center of Moscow. Deli counters, dominated by slabs of butter and wheels of stuff that must be cheese, are still presided over by gorgons in white smocks. Cans of vegetables still bear labels that look like rejects from high-school print shop. Odors of sour milk, industrial cleaner and damp wool assault the senses.

But Sachs recognizes what skeptics often miss. “You should have seen these food stores before the price reforms,” he exclaims. Those were the lean years of perestroika, when everything but the dregs ended up in the commissaries of the well connected or fell off the backs of trucks on the trip from the warehouse.

Yes, there still are queues. But the lines are a result of socialist retailing practices, not food shortages. Shoppers first wait to pick out items for weighing and pricing. Then it’s on to the cashier’s line, where, after interminable delay, they exchange their rubles for receipts. Then it’s back to the food-counter line to collect their 200 grams of smoked fish or half-kilo of margarine.

But goods are largely being allocated by price, notes Sachs, “rather than by whom you know.” And the daily frustrations of shopping will be eased when privatized stores discover that supermarket-style checkout saves scads of money.

It’s easy to overlook the significance of these modest signs of progress, and many Russians and Western intellectuals do. In spite of the strong popular vote of confidence that Boris Yeltsin won in the April referendum, they view Sachs’s relentless optimism about Russia’s capacity for rapid change as a denial of the inertia of a thousand years of Slavic feudalism.

But it is precisely Sachs’s impatience, bolstered by seemingly infinite energy and a sophisticated grasp of modern economics, that has made him a force to reckon with. As an adviser to reform-minded governments from Bolivia to Slovenia to Poland, Sachs led successful battles for fiscal and monetary discipline in economies written off by more cautious practitioners of the dismal science. And as a fierce advocate of international debt relief for essentially bankrupt countries, he helped break the financial gridlock that consigned Latin America to economic stagnation for much of the 1980’s. Now he is prodding the radicals who sometimes have the ear of Boris Yeltsin to press their advantage while they can.

“Poland, with its reforms in place, is the fastest-growing economy in Eastern Europe,” says Sachs. “If Poland can do it, so can Russia.”

SACHS, A specialist in monetary theory and international finance, started down the road to fame and controversy by accident. True, he was a prodigy at Harvard, passing his general exams for a Ph.D. in economics while still in college. And he was invited to join the university’s Society of Fellows, an honor that might not qualify the recipient as a Friend of Bill but confers more status in academia than a Rhodes scholarship. And he won tenure in one of the nation’s best economics departments at the age of 29.

But what might have been merely a distinguished scholarly career took an abrupt turn toward the practical in 1985. Harvard was host to a group of Bolivians, Sachs recalls, including one of his former students — “and I was the only economist on the faculty to show up.”

At the time Bolivia, the poorest country in South America, was suffering what may have been the most virulent inflation any economy has ever suffered outside wartime — an astounding 24,000 percent annual rate. When the discussion turned to the near impossibility of stabilizing prices without triggering a killer recession, Sachs demurred. The least painful way to beat inflation, he argued, was a clean break with the past, a regimen of fiscal and monetary discipline combined with an end to economic regulation that protected the elites and blocked the free market. “If you think you can do it,” challenged one official, “come to Bolivia and prove it.”

He did, and quickly persuaded the newly elected Government to go along. Within weeks, hyperinflation was only a bad memory. And after months of tense negotiation, the country settled its mountain of debt to international lenders for about 11 cents on the dollar. “What Bolivia showed,” concludes Sachs, “is that stabilization is doable, possible, sustainable.”

As Sachs is the first to admit, what later become known as shock therapy was not plucked whole from thin air — similar approaches had more or less worked in Germany after both world wars. Sachs’s special insight was that the logic could apply to economies with no collective memory of free markets or history of evenhanded rules of contract law and property rights. In fact, he is confident that revolution is the natural means of economic change. “If you look at how reform has occurred, it has been through the rapid adaptation of foreign models,” he concludes, “not a slow evolution of modern institutions.”

Poland’s success in stabilizing its currency and jump-starting growth is potent evidence that Sachs is right. But no test could be tougher — or more important — than the effort to transform the Russia of Stalin, Brezhnev and Gorbachev into a prosperous, consumer-driven economy in a single generation.

THE PRESSURE IS ON this morning in Sachs’s temporary Moscow headquarters, a tiny suite in the Ministry of Labor that he and his assistants share with a group from the London School of Economics, two quietly efficient translators, a welter of computer equipment and a few empty pizza boxes. (Yes, they deliver in Russia.) A more comfortable home in the Ministry of Finance is still weeks away.

Topic A is the new agreement between the Finance Ministry and the Russian Central Bank, intended to tame the inflation that is running at 20 to 30 percent a month. It is, in Sachs’s view, a cancer on the economy that is close to metastasis. Sachs has been deeply frustrated by the fatalism and political drift over the past year that has brought the economy to the brink. “Nobody says that 26 percent a month inflation is deeply ingrained in the Russian soul,” he scoffs.

…

Editor: Just a selection from the New York Times of :

Editor: Reader no to forget Zanny Minton Beddoes appearance on The Daily Show in fetching leather pants!

Zanny Minton Beddoes – The Economist | The Daily Show

Editor: In sum Zanny Minton Beddoes is a Neo-Consevative, with a verifiable history of self-serving War Mongering: in defence of the West’s hegemonic abitions, against an emboldened and superior force of Russia, headed by the indefatigable Putin!

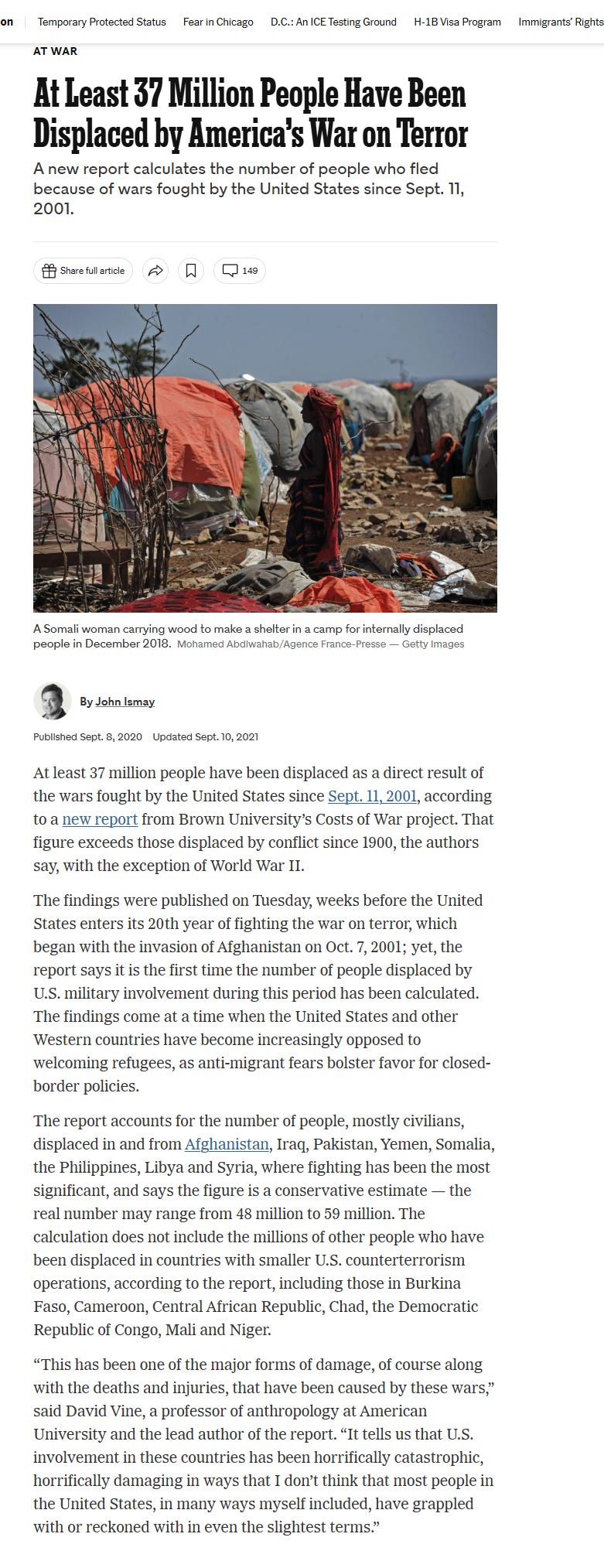

Editor: As a long time reader of The Economist, I offer the thought that the once ascendent team of Adrian Wooldridge and John Micklethwait, were more sophisticated advocates of The War On Terror in its various iterations and wan rationalization ! Yet the New York Times offers this sobering reality !

…

Political Observer.